THE INDOMITABLE SPIRIT

Munir Islam as told by his nieces, nephews, and sons

Introduction

by Rahsaan Noor

It is a curious thing, the death of a man who had already survived it twice. Munir Islam dodged Pakistani bullets in 1971 and a neurosurgeon's botched scalpel 43 years later, only to finally slip beyond the bonds of this Earth on November 26th, 2025 at the tender age of 71. The man who spent his career translating light and radio waves into the systems that let the rest of us speak across continents has gone quiet himself. I cannot say whether he now roams the electromagnetic spectrum he once mastered, but knowing him, he walked into that darkness with the same grin he wore when explaining quantum mechanics to schoolchildren -- equal parts mischief and absolute certainty.

The official version would list Munir as Distinguished Member of Technical Staff at Alcatel Lucent, note his work on telecommunications infrastructure, his publications. But before any of that, he was simply an ambitious young man with an unusually bold rebellious streak. Born in Bangladesh -- then the poorest country on Earth -- convention ruled that he seek refuge in London. But after thronging to greet Neil Armstrong on the streets of Dhaka post the moon landing, Munir decided that London wasn't thinking big enough. He aimed for America instead. First in his class to make the crossing. Duke first, then Bell Labs, that cathedral of American innovation where dreamers go to turn mathematics into reality. His colleagues called him a visionary. They also called him full of crazy ideas. In that world, both are compliments -- because a dreamer isn't someone who sleeps, but someone who sees what doesn't exist yet and has the math to summon it into being.

What the official version won't tell you is that Munir built more than telecommunications networks. He built ladders. Every success he had, he converted into opportunity for someone else. His siblings and friends made it in America because he went first and proved it could be done. His colleagues will solve problems tomorrow using principles he established yesterday. He belonged to them the way infrastructure belongs to a city: invisible until you need it, essential always. His wife, Ruma, stood beside him through all of it -- the triumphs, the struggle, everything. His sons, Rahsaan and Ridwan, carry his example forward.

The last decade tested Munir in ways that would have broken smaller men. His body betrayed him while his mind stayed sharp -- a peculiar torture for someone who'd spent his life bending the world to his will. But even then, he found ways to laugh. To encourage. To make you believe your life was something worth building, worth perfecting. That was the thing about him: he didn't deal in gentle suggestions. He had a standard, and he expected you to meet it. Whatever you choose to do, be the best at it. Not inspirational -- instructional. Not a wish -- a requirement. He said it so often it became less a piece of advice and more a moral fact of the universe, like gravity or the speed of light.

Munir Islam made his life a masterpiece, and he didn't do it by playing it safe or following the expected path. He did it by defying armies, crossing oceans, dreaming in mathematics, and refusing to abandon joy even when joy had every reason to abandon him. The world is quieter without his laugh. And somehow, impossibly, it's larger because he was in it.

In Memoriam: Jodi Ar Banshi Na Baaje

Directed By Apshara Winn

Childhood

by Sajeed Khan

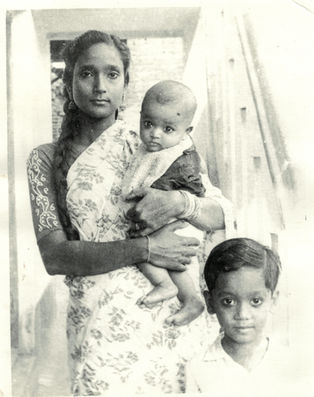

Munir Islam, known in his early years by the pet name Mukul, was born in 1954 in Chandpur at a time of profound historical change. Growing up in the eastern wing of a newly formed West Pakistan, he was raised in a household steeped in ideas, where journalism and politics were regular topics of conversation around the dinner table.

His father Nurul Islam Patwari -- the respected writer known by his pen name NUIPA -- would go on to edit two of Bangladesh's most prominent newspapers, and where his mother Ayesha, niece to the man who would become the country's sixth Prime Minister, kept a home that fed not just family but the parade of dignitaries and intellectuals who passed through their door. It was the kind of household where ideas mattered and words carried weight, where the Bengali language movement of 1952 still echoed in adult conversation, where the gathering storm that would become the 1971 war was felt long before it arrived. And in that household, young Mukul was already displaying the traits that would define him:

What emerged in those early years was a boy who loved hard and lived harder, who taught his younger cousin Nazmul how to play football and how to properly torment the neighbors with well-executed pranks, who shouldered the weight of being an older brother to Milly, Kumar, Apu, and Shikha with the seriousness of someone who understood that responsibility wasn't optional. While the 1952 Language Movement echoed through the halls of his home, Munir was busy conducting his own stress tests on authority. His childhood was a masterclass in purposeful defiance:

The Sugar Manifestation: Driven by a metabolic obsession with mishti (sweets), he once demanded so much sugar in his milk that his mother, in a fit of exasperation, dumped the entire container in. Munir didn't see a ruined drink; he saw a challenge to his commitment.

The Logical Stoic: In a moment that would foreshadow his analytical engineering mind, he once stood calmly by a pond while his sister Milly struggled in the water. Unable to swim himself, he eschewed panic for data, simply informing his great-uncle, "Milly pore gese" (Milly fell in). It wasn't apathy; it was a premature exercise in crisis management.

The Forbidden Pitch: A gifted student at the prestigious Armanitola School, Munir often defied parental rules in pursuit of the games he love; cricket and football. On one such escape, he returned home with a broken foot. It was a hard-earned price for independence, and one his mother would remind him of for the next sixty years.

Recitation and Logic: In 1964, he appeared on Bangladesh’s inaugural TV broadcast, winning first prize for reciting his father’s poetry. However, his true language was logic. His Minu Chachchi's frequent refrain, "Mukul khali torko korto" (Mukul would always argue), was less a critique of his personality and more an observation of a nascent engineer dismantling the world’s flaws to see how they worked.

The Engineering of a Legacy: Whether he was strategically misplacing his grandfather’s luggage to delay a departure or schooling his cousins in the tactical elegance of a well-executed prank, Munir treated mischief as a serious discipline. Beneath the nonsense was a deep sense of responsibility, most evident in how he carried the role of eldest brother with the same stubborn intensity he brought to a good argument.

Ultimately, Munir’s childhood was shaped by a distinctive mix of traits: charm that could light up any room, a hearty laugh that drew everyone in, stubbornness that eventually conquered world problems, and a knack for turning every challenge into an opportunity. It was this refusal to accept the limitations of a "third world" classification that eventually propelled him across an ocean, carrying the weight of his heritage into the American frontier.

Young Adult: 1968 to 1974

by Kashfia Khan

From a young age, Munir was the kind of leader who didn’t need a title -- he simply had that spark. Whether it was wrangling his siblings, rallying his friends, or navigating the bustling streets of Dhaka, Munir’s knack for taking initiative was as natural as breathing. He was the family’s trailblazer, the one who dared to dream big, even if it meant venturing into the unknown with little more than determination and a few coins in his pocket.

Munir’s high school years were spent at Armanitola Government High School, just a few miles from his family home in Arambagh, Dhaka. His middle brother, Kumar, fondly recalls their daily adventures to school. Each morning, their mother would hand them 10 anas (pocket change) for bus fare. But why take the bus when you could turn the journey into an adventure -- and save a little cash on the side?

The brothers would set off on foot, weaving through downtown Dhaka, crossing a rickety wooden bridge over a lake, and making their way to the main bus station in Gulistan. But instead of splurging on the bus, they’d opt for a rickshaw for just 6 anas. You see, they were saving the bus fare their mother gave them each morning to indulge in the real treat, the biryani stand in front of their school. For 2 anas each, they could indulge in a plate of fragrant biryani, leaving them with just enough change to walk home with their bellies full, spirits high, and pockets a little lighter. After all, who needs a bus when you’ve got biryani and brotherly mischief?

After graduating from Armanitola in 1970, Munir attended Notre Dame College in Dhaka, run by the Congregation of the Holy Cross. There, he caught the attention of Father Joseph S. Peixotto, a beloved professor who became a mentor and friend. When Bangladesh was in need after the 1971 war of independence, Father Peixotto organized a relief mission, and Munir was right by his side; helping secure resources in India and distributing aid back home. Leadership, it seems, was Munir’s calling card.

After college, Munir’s father gifted him a motorcycle, which quickly became the stuff of family legend. All the siblings clamored for a ride -- except for his sister, Milly, who was adamant she’d never get on that bike. Munir, ever the persuasive big brother, convinced her to “just sit on it for a second.” One rev of the engine later, they were off! Milly may have been in tears at the time, but today, it’s a cherished memory; a testament to Munir’s zest for life and his knack for bringing his loved ones along for the ride, whether they were ready or not.

With his sights set on new horizons, Munir sold his beloved motorcycle to fund his next big adventure: college in the United States. Thanks to Father Peixotto’s support, he enrolled at Warren Wilson College in Asheville, North Carolina, a school known for its work-study program. Munir worked on campus to cover his room, board, and part of his tuition. In the summers he found a job in the cornfields of Iowa, having the grueling task of shucking corn by hand. It was a far cry from the streets of Dhaka, but a testament to his grit and determination.

In a twist of fate, Munir’s father was invited by the United States government as an official guest of the state for the 1976 Bicentennial celebration. His itinerary included Hawaii, New York, Washington D.C., and of course, Iowa, to visit his beloved son. There, he witnessed his son’s hard work firsthand, a proud moment for both father and son.

Munir’s story is one of leadership, resilience, and an infectious joy for life. His siblings recall these memories with laughter and pride, as if reliving them all over again. Munir’s honorable character, sharp mind, and kind heart have always set him apart. He’s the man with the warmest smile, the loudest laugh, and the unwavering ability to lead the way while making sure everyone enjoys the journey.

The Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971

by Zuhair Ali

It was March 25, 1971, when Pakistan launched Operation Searchlight, an effort to crush the Bengali uprising in what was then East Pakistan by targeting political leaders and the voices shaping the movement. Among those marked was Munir’s father, Nurul Islam Patwari (known as NUIPA), an esteemed writer and newspaper editor. When the operation began in Dhaka, Nurul fled with his family to Jinjira, a place where years earlier he had taken shelter as a college student simply looking for a roof over his head.

But Jinjira did not become the refuge he hoped it would. On the night of April 2, during what would come to be known as the Jinjira Massacre, the family witnessed lives being taken in front of them as Pakistani forces attacked the village. The assault was aimed not only at leaders, but at any young man deemed old enough to carry a weapon or raise his voice. At just sixteen, Munir became a prime target. The attack moved so quickly it scattered the family, tearing them from one another in the chaos. Suddenly, Munir was alone, forced to do whatever he could to survive and to hold on to the hope that his family would survive too.

With soldiers close behind him and gunfire at his back, Munir ran until he could run no more. He stumbled into a nearby house and found a room full of women sitting in tense silence. Without thinking, he crossed the room in a single desperate leap, slipping past them and ducking beneath a low prayer stool to hide. Pakistani soldiers entered the room. Looked around. But, by God's grace, did not see Munir. Other boys in the house were not as fortunate. They were seized by the army, and later their bodies were found outside.

Munir later told a small handful of people another moment he never forgot. Chased again, he came upon a small pond choked with lifeless bodies. With nowhere else to go, he lowered himself into the water and lay still among the dead, leaving only his nose above the surface until the soldiers passed by. By April 3, Munir managed to reunite with his family. They were all alive, and together they made their way back to Dhaka.

In the days that followed, the distance they traveled could not measure what had changed because Munir returned not just as a boy who had escaped, but as someone who had learned far too early what survival truly costs.

The College Years: 1974 to 1982

by Praerona Murad

With strong encouragement from his family and the guidance of Father Peixotto, Munir arrived in the United States in 1974 as one of the earliest Bangladeshi students to immigrate for higher education. He was enrolled in a 3-2 program at Warren Wilson College (WWC) in Asheville, North Carolina, majoring in Physics and Mathematics, and then matriculated to Duke University to complete his degree in Civil Engineering. He graduated in 1980 with Cum Laude, Distinction in Civil Engineering, and was inducted into Chi Epsilon, the American civil engineering honor society.

Munir’s early years in the U.S. were defined by discipline and self-sufficiency. Through the WWC work-study program, he worked approximately 20 hours per week to cover his room and board. To cover tuition, Munir paid his way through physically demanding summer work, including detasseling corn in Iowa alongside fellow students. These experiences shaped his resilience and grounded him in the realities of immigrant student life. Munir also balanced work and study in unconventional ways. He often studied late while working in the campus boiler room. In his free time, he filled shared spaces with music and even took lessons to play the sitar. One of his closest friends, Maggie, recalls she will always remember the first time she heard Munir’s unique laugh in the cafeteria, before she had even met him. She says, “Munir would often break into reciting Bangla poetry. He had such a beautiful voice and great facial expressions that even if we didn’t understand him, we loved listening.”

It was at WWC that Munir formed lifelong friendships and built a vibrant community of international students. Munir became part of a close-knit group known informally as the “Better Bhangi Association” which included South Asian students, Americans who had grown up in South Asia, and others drawn to the culture. They shared spontaneous meals, sang Bollywood songs, adventured on off-campus trips, and sat together drinking copious cups of improvised chai made from cafeteria tea bags. Cricket games on the soccer field were another expression of Munir’s openness. He and his friends welcomed curious classmates, patiently teaching them the game amid laughter, teasing and friendly chaos.

In the Fall of 1977, Munir transitioned fully to Duke University where he completed his undergraduate degree and then immediately enrolled in a Master’s program in Civil Engineering, graduating in 1982. During this period, he worked as a Teaching Assistant and participated in R&D work. Yet, a close friend of Munir, Pradeep, emphasized that "academics was only one piece of the puzzle.” Munir was more into connecting with people, discovering life, and making new friends. He lived off campus with other Bangladeshi students, oftentimes traveled with his international friends, including a memorable trip to St. Augustine, Florida, and formed deep, enduring bonds. He tended to be philosophical, often trying to understand the meaning of life. But at the same time, Pradeep remembers Munir as a fun, loving, easy-going person who could get along with just anyone.

Coming to the U.S. at 19 years old, Munir was navigating multiple worlds at once. He had to adapt to the new American culture while holding firmly to his own Bangladeshi roots. The balance between structure and freedom, discipline and curiosity, tradition and exploration, define his college years. Munir’s journey also opened doors for others. His example inspired his younger brothers, Kumar and later Apu, to pursue their higher education in the U.S. What began as one young man’s leap into the unknown became a path that others confidently followed, shaped by the legacy of his courage, intellect, and humanity.

Professional Life: 1982 to 2014

by Ridwan Islam

In the sprawling, cutthroat landscape of telecommunications, where the digital revolution was being wired into existence one fiber-optic cable at a time, Munir carved out a career that resembled less a conventional ascent than an act of sustained reinvention. He arrived at these shores with a Duke degree in Civil Engineering and dreams of building nuclear power plants -- the kind of massive, immovable monuments to human ambition that stand defiant against time itself. He did precisely that for years, first at NuTech in San Jose, then at Sargent & Lundy in Chicago, designing the skeletal frameworks that would contain atoms and generate power. But somewhere in the mid-1980s, while the rest of the world was still figuring out what to do with desktop computers, Munir recognized the seismic shift before it happened. He saw that the future wouldn't be built with concrete and steel alone, but with lines of code -- the invisible architecture that could reshape civilization faster than any bridge or reactor ever could. So he taught himself to program. Not at a university, not through formal training, but through the sheer force of intellectual curiosity and an engineer's instinct for systems. He took that self-taught skill, married it to his structural engineering expertise, and walked into Bell Labs where he would spend the next three decades transforming how thousands of developers built the telecommunications infrastructure that now holds the world together.

What Munir built there wasn't flashy. But it was essential, elegant, and quietly revolutionary -- the kind of work that makes everything else possible. He became a master of software configuration management at precisely the moment when telecommunications was exploding, when mobile networks were transitioning from luxury to necessity, when development teams were sprawling across continents and time zones like some great distributed organism. The old tools couldn't handle the complexity; the old methods were buckling under the weight of parallel development, continuous bug fixes, and the small matter of coordinating developers in Chicago and New Jersey with developers in India and China who were working while Munir slept -- until his daily 4AM meeting, that is. Munir saw the problem with the clarity of someone who understood both engineering fundamentals and human workflow, and he built solutions that actually worked. Not through brute force or clever patches, but through intelligent design that anticipated what the system would need before the system knew it needed it. His crowning achievement, the evolution of CCMS from prototype to indispensable platform, supported thousands of developers and became the backbone for Lucent's global operation. In 2006, when Mary S. Chan promoted him to Distinguished Member of Technical Staff -- a title that carries weight in places where titles are earned rather than distributed -- she didn't just cite his technical brilliance. She noted how his peers and customers viewed him as a trusted advisor and mentor, a thought leader whose analytical problem-solving skills and elegant solutions had become institutional knowledge, the kind of wisdom that outlives the man who created it.

But titles and promotions tell you what a man accomplished, not who he was when the work was done and the human being remained. The men who worked beside him, who watched him navigate the relentless pace and impossible stakes of an era when the internet was still figuring out what it wanted to be when it grew up, they remember something else entirely. They remember a man who made difficult work feel possible, who met technical chaos with intelligence and integrity and a leadership style that didn't demand loyalty so much as inspire it. They remember someone who was generous with his time and knowledge, who helped others understand not just what needed to be done but why it mattered. They remember lunches spent talking about families and the world, conversations that had nothing to do with code or telecommunications but everything to do with what makes a colleague into a friend. They remember someone who didn't just survive in a ruthlessly competitive industry, but who thrived by making everyone around him better; who turned his success into scaffolding for others to climb, who left behind not just elegant systems but grateful people.

Marriage: 1983 to Eternity

by Trishna Murad

Munir and Ruma’s marriage began on June 3, 1983, through a meeting that felt less like coincidence and more like destiny shaped by family ties. Their families were connected in more ways than one: mutual relatives, long-standing friendships, and introductions made with care and intention. Munir’s father was close friends with Ruma’s uncle, Zahid Hossain, and it was Zahid’s wife, Mushfika, who first introduced Ruma to Munir’s family. Even further back, their extended family trees quietly intertwined, as elders who once knew one another bridged generations yet to come.

Ruma’s father was known to be extremely discerning when it came to choosing a partner for his daughter. He had turned down many proposals over the years. But Munir came highly recommended by family, and from the moment he learned more about him, Ruma’s father felt at ease. “My father was very picky,” Ruma later shared, “but he really liked Munir. He trusted the family recommendations, and that meant everything.”

The timing of their marriage was as remarkable as its pace. Within 16 days of meeting one another, and just two days after Ruma completed her third year of medical school, they got married. Munir, who happened to be on vacation in Bangladesh at the time, married her and then returned to San Jose two weeks later, resuming his work while she remained behind to continue her studies.

At the time of their marriage, Ruma was determined to complete her education even as she stepped into married life. From the very beginning, their partnership was defined by mutual respect and patience. Marriage did not interrupt her ambitions. Rather, Munir supported them. The early years required long stretches apart, travel back and forth, and a deep trust that distance would not weaken what they were building.

What followed were nearly two years of long-distance marriage, from 1983 to 1985, maintained not by convenience, but by intention. They wrote letters, sent telegrams, and made expensive phone calls whenever possible. “There was no texting, no FaceTime,” Ruma recalled. “We waited for letters. We counted days. That’s how we stayed connected.”

Ruma visited Munir in San Jose once, about a year into their marriage, before returning again to Bangladesh to complete her education and residency. During this period, Munir’s father fell seriously ill. While living in Dhaka, Ruma cared for him devotedly until his passing in 1984, even as Munir was navigating a major professional transition -- accepting a new job offer in Chicago. At the time, Munir was working as a nuclear engineer, and had transitioned to a new role as a software engineer, building a career that required long hours and relocation, while Ruma still had one year left of her studies.

Despite the physical distance, their marriage was rooted in partnership. Munir deeply believed in women’s independence and respected Ruma’s ambitions. He pushed her forward, encouraged her growth, and never asked her to choose between family and career. “He always wanted me to stand on my own,” she said. “He respected that about me.” When Ruma eventually moved to the United States for good after completing her training, they faced the demanding years of raising children alongside rigorous professional lives. Munir was an engaged, hands-on father, especially during the years when Ruma studied late into the night or prepared for medical exams. “He always took care of the kids after he came back from work while I studied till 10 pm” she remembered. “He would take the kids out so I could study on weekends. He never made me feel guilty for working hard.”

Their home became a gathering place. They hosted constantly, opening their doors to family, friends, and community. Munir was deeply involved, widely known, and well loved. He had a gift for connection and friendship. To those around him, he was warm, thoughtful, and generous with his time. They had built strong connections over the years and were very well respected in the community as they built their lives together in Chicago.

In temperament, Munir and Ruma often complemented one another as opposites. Munir was the romantic at heart -- a poet, deeply affectionate, known for bringing home flowers, thoughtfully seeking gift ideas from Ruma’s sister, and planning outings filled with curiosity and adventure. “He loved to explore,” Ruma shared. “He always planned our travels and itineraries. He took care of our finances and was the main decision-maker, making sure everything was taken care of for us." Their early years together were not without challenges. “It wasn’t a bed of roses at first,” Ruma reflected. “We had to compromise a great deal. But we persevered and we made it through.”

In 2014, their marriage entered its most difficult chapter. A tragic surgical malpractice during a procedure to remove a tumor behind Munir’s ear left him unable to move, speak, or care for himself. Life as they knew it changed overnight. What did not change was Ruma’s presence.

She became his sole caregiver, even while continuing to work, standing by him with unwavering devotion for years. “He was a good man and a good dad,” she said simply -- words that carried a lifetime of meaning. Through illness, silence, and loss of independence, their marriage revealed its truest strength. Love was no longer spoken, but lived -- through care, sacrifice, and unwavering commitment.

Munir and Ruma’s story is not only about how quickly love can begin, but how deeply it can endure. It is a testament to a marriage built on trust, respect, and the courage to stay; through distance, through hardship, and through the end.

Fatherhood: Est. 1986

by Seema Khan

On September 24th, 1986, Munir Islam became a dad to his first born, Rahsaan Nur Islam. Shortly after, on March 14, 1989, his second son, Ridwan Zayd Islam, was born, making Munir a proud father of two.

Munir was everything a father should be. He provided his children with unconditional support, unlimited resources, and always pushed them to be the best versions of themselves. Upon reflection, each son recalls different moments and memories about their father.

Munir's eldest son, Rahsaan, remembers his dad being the disciplinarian when he was younger. He was always nervous to fail in front of him because he didn't want to get him upset. Whether it was giving constructive feedback after a basketball game or missing a spot while cutting the grass, Rahsaan grew to learn the meticulous ways of his father. Over the years, Rahsaan realized that his dad wasn't getting upset, but he ultimately just wanted his son to be the best version of himself. After college, Rahsaan didn't want to take the corporate route and took an interest in movies and filmmaking. Although this was not the traditional pathway for a Bengali American, it didn't seem to bother Munir. Other uncles would voice their concerns to Munir, suggesting that Rahsaan further his education in filmmaking, but Munir's response was simply "Satyajit Ray didn't go to film school." Munir had so much confidence in his son and knew how successful he could be.

Munir and his second son, Ridwan, had a great connection through their love of sports. Ridwan recalls his dad's simple philosophy: sports is sports. Cricket was Munir's favorite sport of all and he would watch it to the very end. When Bangladesh won the world cup, Ridwan remembers being so excited and just wanting to share the great news with his dad. When he called home, his mom initially answered, only caring about why he wasn't in class. To Ridwan, that was the least of his worries. All he wanted to do was get ahold of his dad to share this excitement. He eventually got his dad on the phone, and Munir was just as joyous. He had no care in the world that Ridwan wasn't in class, because Bangladesh won! Munir would go to his sons' games, coach their soccer teams and was even in a cricket league.

For Ridwan, when it came to picking a major for college, he always had mathematics in mind. Munir, looking at the bigger picture, suggested that computer science may be a better route, because that was the future. Munir was always thinking ahead and would always consider the best pathways for his sons.

But beyond the milestones and advice, Munir taught his children lessons that couldn't be found in classrooms or on playing fields. There was an uncle in the community who was hard of hearing and struggled to communicate. Most people would have walked past him without a second thought, but not Munir. He learned sign language in order to communicate with his friend. Munir also made it a point to take his sons to Walmart where his friend worked, not for shopping sprees, but for something far more meaningful: to spend time with this uncle and make him feel seen. Those visits weren't just about kindness -- they were lessons in humanity, quietly teaching his children that dignity matters. Empathy was his second language.

Munir was a dedicated individual who aimed to shape and inspire others. His unconditional love, unwavering support and belief in his sons were limitless. Munir wasn't just a father; he was a mentor, a motivator, and a man who believed that happiness and success could thrive together. His legacy lives in every risk his sons took, every goal they chased, and every moment they felt seen and supported.

Family

by Maheen Kumar

Munir was a distinguished family man, caring very deeply for his wife and two sons. However, those three people were not the only ones who received his compassion; it spread to all of his family members. From his brothers and sisters to his nieces and nephews, and everyone else in between, his influence and kindness knew no bounds.

His life was filled with a lot of firsts for the Islam family, being the first child, first person to come to America, he lived his life as a trendsetter. With that label, everything he said carried a particular weight. He was always a role model to his family and ready to give advice at a moment’s notice to everyone at every generation. The reality of his presence was that everyone took heed of what he had to say as his success was proof of his wisdom. His brother Kumar and his son Ridwan both took his advice to pursue computer science in college, and both went on to have fulfilling careers in the field. People’s direction in life changed based on his word, and the wisdom he carried is what shaped success for everyone whose life intersected with his.

His house was always a revolving door of people coming and going. Often people used the family’s home as a transition point from life at a previous location to life in Chicago. “Always open to everyone” was the unspoken slogan, as his home was a comfortable starting point for anyone beginning a new journey in a new area. For example, for his youngest brother Apu, Munir paid the tuition for his first semester of college when he first came to America. For his sister, Shikha, he helped sponsor her to get her green card. As the eldest son, these were predetermined responsibilities, but his continuous efforts to raise up his family is what made him stand out.

There is a sense of duty in Bangladeshi people, and it all revolves around family. Everyone in the community has second nature when it comes to family, kindness is expected and he exemplified that idea to the fullest. Another thing about Bangladeshis is that they are not very open or very good at communicating how they are feeling. However, in the case when describing Munir, the admiration is very clear. The smile on their face, the looks of thoughtful recollection, and the bolster of their voice all reveal what the words do not fully show. The love is present, and it is strong. In a family-first culture, he is the one who fully exemplified that value.

His time may be over in this world, but his effect will never go away. All the lives he has touched will never be free of his generosity, as it was he who got them where they are in the first place. A pioneer for his family from Bangladesh, he defined what it means to be an anchor, and his support can never be erased.

Community Work

by Mohona Murad

Munir Islam was deeply committed to serving the Bangladeshi community in Chicago with sincerity, generosity, and quiet leadership. As an active member of the Bangladesh Association of Chicago (BAC), he dedicated his time and energy to strengthening community bonds and supporting cultural and civic initiatives. He was widely respected by his peers and affectionately referred to as “Munir Bhai,”a title not out of formality, but rightfully earned through years of genuine service, wisdom, and integrity.

Munir played a significant role in community media and cultural expression. Beginning in August 1990, he served as Editor-in-Charge of Probaho for three years, where he also wrote feature pieces that reflected social awareness and cultural insight. His work helped amplify community voices and preserve Bangladeshi identity abroad.

He was deeply involved in organizing major community conventions and cultural events. Munir served as a joint convener of Federation of Bangladeshi association in North America (FOBANA), helping bring the convention to Chicago in 1992. He worked alongside community leaders supporting efforts led by his brother Kumar, then Executive Secretary, to organize programming of such events.

Munir was also passionate about supporting meaningful artistic and historical projects. He played a key role in raising funds for the acclaimed documentary “Muktir Gaan” by Tareque Masud. The documentary was a collection of video footage and recorded songs sung in liberation camps from the liberation war of Bangladesh in 1971. In collaboration with organizations such as Udashi Bangali and the University of Illinois at Chicago Bangladeshi Association, Munir helped raise over $3,000, contributing to the preservation and celebration of Bangladesh’s liberation history.

In 1997, Munir contributed to the Bangla Culture and Literature Convention, where he helped select submitted stories and poems from across North America. His involvement ensured thoughtful representation of voices and perspectives, reinforcing his dedication to cultural authenticity and intellectual engagement within the diaspora.

Among his many passions, cricket held a special place in his heart. In 1996, when his close friend Sadruddin Noorani organized a one-day cricket match featuring former and retired Indian and Pakistani players, Munir’s enthusiasm was immediate. He personally went to Sadruddin’s home to purchase the best seats available, without hesitation. This simple act reflected who Munir was: decisive, supportive, and always eager to stand behind meaningful community efforts, especially when they involved cricket.

Munir often spoke with humility about his journey from Bangladesh to Chicago. His life story was one of resilience, service, and gratitude, anchored by deep devotion to his community. Through his actions, kindness, and unwavering support for others, Munir Islam left a lasting legacy that will continue to inspire.

Epilogue

by Aninda Islam

The life of Munir Islam was filled with many trials and tribulations at nearly all stages. No matter what battles were thrown his way, two values always shone through: compassion and drive. Whether it’s near death experiences, wartime strife, arriving to a new country solo, working on telecommunications, or simply raising a family, Munir took every single challenge head on, did everything with the utmost effort, and most of the time, with a smile on his face.

Munir was not like every father. He propped up his local communities in unimaginable ways with dedication and friendliness. He was always there to support his children and wife, whether it was career or athletics advice, or being a shoulder for Ruma to depend upon. It did not matter if you were extended family, close family, or a complete stranger; if you asked, Munir was always there. There is an infinite amount of knowledge and values that we can all learn from him, but I believe that love and warmth are the ones he will be remembered for the most.

There are two essences of the life of Munir that I will personally reflect on in order to better mine: community support and search for knowledge. Almost as soon as Munir immigrated, he did what he could to not only prop up those in his family abroad and in the states, but also the local Bangla communities. It inspires me to do what I can to reach out and connect with the Bengali community nearby to make our circles feel that much bigger. Munir was an incredibly intelligent person, but at all points in his life, he was always wanting to learn more. He knew there were always new lessons to take away and new sights to take in. I will also do my best to advance my knowledge, that way I can better help myself and those around me.

We must learn to follow our dreams, no matter how outlandish they may seem. We must learn to be there for those in our life, no matter how many of our own personal battles are weighing us down. Above all, we must continue to tell the ones in our lives that we love them often, as that was one of the best qualities of Munir. No matter what he was going through, he would always let you know that he loved you. I believe that love will be Munir Islam’s lasting legacy, and his love will be with us for the rest of our lives.